But before I get into that, let's review the text first:

Finally, be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his might. Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil. For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. Therefore take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm. Stand therefore, having fastened on the belt of truth, and having put on the breastplate of righteousness, and, as shoes for your feet, having put on the readiness given by the gospel of peace. In all circumstances take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming darts of the evil one; and take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, praying at all times in the Spirit, with all prayer and supplication. To that end keep alert with all perseverance, making supplication for all the saints, and also for me, that words may be given to me in opening my mouth boldly to proclaim the mystery of the gospel, for which I am an ambassador in chains, that I may declare it boldly, as I ought to speak. Eph 6:10-20 (ESV)Ready? Let's go.

There should be no doubt (especially after everything we've gone through) that the image St. Paul is using is of the classic Roman soldier, though pared down. Why? Well, lets look at why I think he listed what he did.

And, yes, this is just opinion. I've really got nothing other than my overactive imagination and a healthy dose of military history to back up my hypothesis.

What do we have in the kit of the "Christian soldier?"

- Belt of truth

- Breastplate of righteousness

- Readiness given by the gospel of peace (as shoes)

- Shield of faith

- Helmet of salvation

- Sword of the Spirit (the word of God)

But why would the illustrious writer of half the New Testament not advocate for greater armaments and armor in spiritual warfare. After all, this is the guy who wrote "we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places." v. 12

The answer is simple: the war is over.

The war, which began in the Garden at the roots of a tree, ended on the branches of a tree placed on a hill just outside Jerusalem.

When Jesus received the sour wine, He said, "It is finished," and He bowed His head and gave up His spirit. John 19:30

But the angel said to the women, "Do not be afraid, for I know that you seek Jesus who was crucified. He is not here, for he has risen, as he said." Matthew 28:5-6a

And while they were gazing into heaven as He went, behold, two men stood by them in white robes, and said, "Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking into heaven? This Jesus, who was taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw Him go into heaven." Acts 1:10-11So, then, the war is over. Why then do we need armor? The war may have ended, but the enemy still prowls about. What we have is an odd mix of "stay-behind" operations, collaborators, and occupation force.

We live in occupied territory. Since the fall, the "prince of this world" has held sway over us, with collaboration from our own nature. But the enemy was defeated, yet still holds control over at least this small territory. Which means we, who know the rightful king, are not members of the regular military, but resistance fighters.

(Its kinda like that, except the enemy is hyper-competent, and none of the guards can be bribed with pastries.)

Now, I'm not saying we are to be performing combat against the enemy. We are not that well armed or armored. A better parallel would be the White Rose, a non-violent anti-Nazi protest in Germany during WW2. They "fought" with words, images, publications, and even graffiti.

The Greek word κῆρυξ - "proclaimer, herald" - fits our duties better than soldier. We are not to be liberators, combat engineers, or warriors. Instead, our duty is to run town-to-town with news of the victory. Think the first marathon runner, just without the pass-out-dead ending.

Consider the final verse of the song "In Christ Alone," especially the second to last line.

Our duty is to stand firm, at all times, as St. Paul extols in his letter to Timothy.No guilt in life, no fear in death—This is the pow’r of Christ in me;From life’s first cry to final breath,Jesus commands my destiny.No pow’r of hell, no scheme of man,Can ever pluck me from His hand;Till He returns or calls me home—Here in the pow’r of Christ I’ll stand.

Preach the word; be ready in season and out of season; reprove, rebuke, and exhort, with complete patience and teaching. For the time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own passions, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander off into myths. As for you, always be sober-minded, endure suffering, do the work of an evangelist, fulfill your ministry. 2 Timothy 4:2-5As a side note, Paul is telling young pastor Timothy that he is to (1) preach the Gospel at any and all times, (2) keep from bending to society's whims, (3) keep from telling people what they want to hear, (4) stand firm in the truth taught in Scripture.

Back to the metaphor, and more specifically why St. Paul chose the pieces he did to represent the aspects listed.

We'll start passively, with defensive gear and work up to the "fun stuff." And, since the order Paul used basically follows that, I'll stick to it.

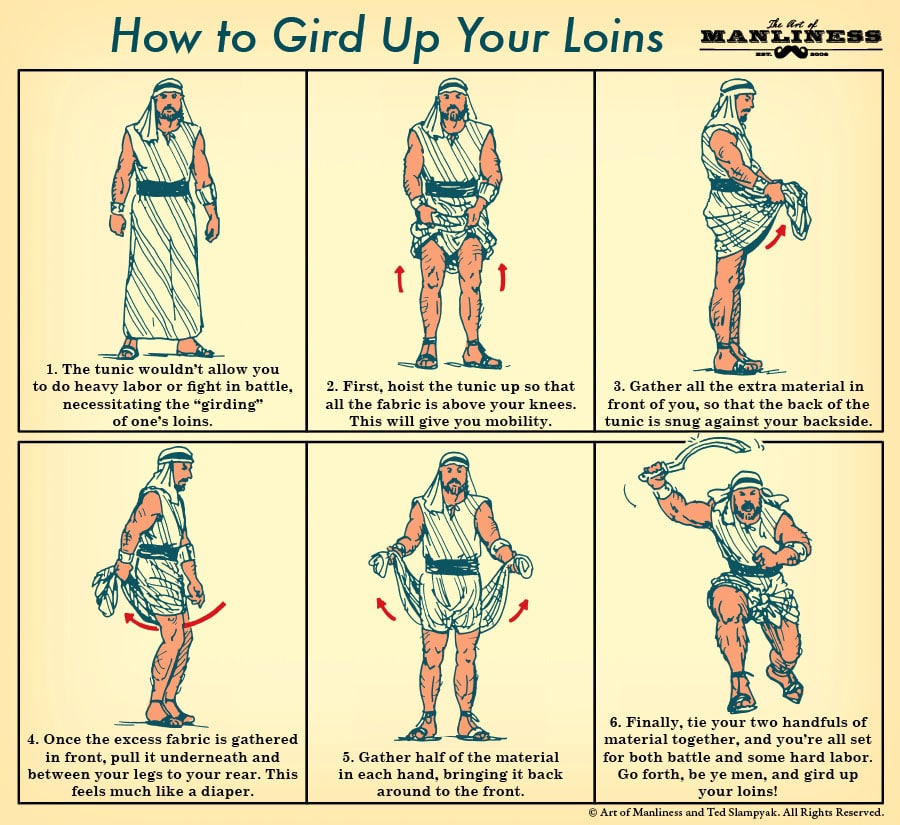

The "Belt of Truth" is first. We've looked at the leather belt-like device worn by the Romans and Greeks, as well as the "lower extremity" armor from the Middle Ages. The purpose and concept of this piece of kit in part falls under the same sort as, to be blunt, the jock strap and the cup worn by male athletes. The other major purpose is mobility. Remember, most people wore floor-length tunics in St. Paul's time. When going into battle, soldiers would "gird their loins:" pulling the extra material up to create shorts. The Art of Manliness has a short little blurb on it, along with a decent step-by-step image on how.

So why is "truth" protecting a soldier's soft bits? Consider. As a Christian, we are to adhere to the Truth. By turning from said Truth, we risk our most vulnerable assets taking control: our Emotions.

(Okay, enough giggling, lets move on.)

Next in the kit is the "Breastplate of Righteousness." This is the only piece of armor Paul allows us (unless you count the helmet and shield, and I'll get to why I'm not). And nothing says its a full torso armor, the cuirass. Which means we only have armor protecting our front half from the waist up. That's not a lot of protection. How does Paul expect us to fight like that? Oh, that right, we're not the ones fighting.

("I mean, sure, its a bit boilerplate, but the darn thing works like a charm. Gonna split the royalties with Marty once we get the patent." - Dr. E. Brown, 1885)

So the breastplate is only for defense, and passive at that. And what does it protect? Our heart. Now, we are not saved by our righteousness, but it works in conjunction with the Law to keep us "in line." That would be the Third Use: the curb. As a Christian we are now free to be able to follow God's Law, though due to our sin we will continue to fail. And that is where the righteousness comes in. It isn't our's that we wear, but Christ's.

The "readiness provided us by the Gospel" rounds out the apparel side of the kit. Boots can be argued to be the most important piece of a soldier's uniform. Being able to protect your feet is spectacularly important, especially to infantry. Think about it. Marching, running, standing patrol. You feet take a beating, and need protecting. Not just from combat, but terrain, injury, and disease. And you need the right footgear for different scenarios. Flip-flops are for the coast of Hawaii, not the coast of Norway, for example.

(Having breathable clothing makes sense in the desert, but not so much a few miles away from Siberia.)

This is the one that connects back into the legendary founding of the marathon. Think about it. To prepare for the race, you need good running gear. The whole story of the first man to run 26.1 miles was to deliver a message of hope and victory. Likewise, we are equipped by the Gospel to go out into the world and proclaim the news that Christ is risen, victorious over death.

Next up: the "Helmet of salvation." As anyone who's ever worked in construction can tell you, wearing protective gear on your head is more than just a good idea or fashion statement. Cowboys wear stetsons to keep from getting sunburn on their squinted eyes. Bikers wear helmet to keep from looking like they're in South Dakota. NFL players wear helmets so you don't see their dumb haircuts. (Seriously, why do football players have hair that would make Rapunzel jealous?) Clearly headgear is important. Why? Because it protects your brain-box from getting squished.

(Especially is your friends ever elect to use you as a battering ram in a rescue attempt.)

I feel like this one should be really obvious as to why Paul picked it. The helmet protects the mind. Salvation is what we need after relying on our reason and strength. Remember, it was a human mind that thought the idea of being smarter than God was a good idea. Hence our need for Christ to come.

You may have noticed I skipped the "Shield of Faith" in the line-up order. Why?

Because its important.

The "Shield of Faith" is the actual defense. Remember, St. Paul is using a metaphor, based on the military of his time. How did the armies of Rome enter battle? In a line, shoulder to shoulder, with shields up. Our faith is not just a individual, but corporate (group) as well. Hence why we confess the Apostles' or Nicene Creeds at each worship service.

(You! Shall not! Pass!)

Think about it. How powerful a defense is a single shield? Quite a bit, especially in the hands of a trained warrior. But how powerful is a wall of such shields? No horde will be breaking through that line when someone calls "red rover."

Or is it...

The "Word of God," or, as is clearly expressed in the first chapter of John's Gospel, Christ Jesus, is the Sword of the Spirit. Wait, Jesus is the sword? But doesn't the Bible describe Him wielding a double edge sword (which may or may not be in His mouth)?

Well, yes. Because the words are the weapon. And if Indiana Jones has taught us anything, its that the pen is mightier than the sword. Or at least mightier than Nazi eyes when you spray ink in their faces.

(Things Indy hates: 1- being called "Junior" 2- Grammar Nazis 3- Regular Nazis 4- Snakes)

But, remember, Jesus is the Living Word of God, so, Jesus is the Sword. And since the Word of God is Scripture, the Bible is the Sword.

So the only weapon is Scripture. Now that doesn't mean there are not other "weapons" in the Christian's arsenal, but that's for my metaphor, which is not inspired and inerrant, like St. Paul's is. And I'll delve more into that later. Be aware, it's my teaching tool, not official doctrine of any particular denomination, not necessarily guaranteed to be 100% in line with Scripture. I hope it is, but I'll concede ahead of time a screw up is likely.

And there's my take/understanding on St. Paul's "Armor of God." My spin on it soon to come.

(And, yes, it'll be multi-part, so I can focus on some aspects I think are of particular importance to the Christian Knight serving his King in this modern and depraved age.)

.jpg)