(*snicker* "civilized...")

But before I get into that, let's review the text first:

Finally, be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his might. Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil. For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. Therefore take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm. Stand therefore, having fastened on the belt of truth, and having put on the breastplate of righteousness, and, as shoes for your feet, having put on the readiness given by the gospel of peace. In all circumstances take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming darts of the evil one; and take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, praying at all times in the Spirit, with all prayer and supplication. To that end keep alert with all perseverance, making supplication for all the saints, and also for me, that words may be given to me in opening my mouth boldly to proclaim the mystery of the gospel, for which I am an ambassador in chains, that I may declare it boldly, as I ought to speak. Eph 6:10-20 (ESV)Now, on to the historic reality. This one is at least easier to grasp, maybe, since there are more fictionalized accounts of Rome.

(Is that not why you are here?)

Like the Greeks, the Romans present a very long, very convoluted, very colorful history. A kingdom, then a republic, then an empire, then a divided empire, then it collapsed, with at least one successor state claiming the title. Most of us are probably at least passingly familiar with "classic Rome" (republic through empire). I'll try to encapsulate the history, then sum up the military, since this is the visual that St. Paul was working with. After all, the soldiers were standing outside his cell when he wrote it.

There are three parts to Rome's history, though the last portion, the Empire, can be divided into multiple sections. I'll deal with that kerfuffle when we get there.

The Kingdom of Rome ran from 753 to 509 BC. The Roman Republic 509-27 BC. The Roman Empire lasted from 27 BC - 480/1453 AD (depending on which version of the empire we're considering).

Rome's founding (not the myth regarding twins raised by wolves) was before 700 BC. Greek historian Timaeus places its founding in the year 814 BC (38 years before first Olympics). Others place it in the 750s. So I'll just say the city of Rome was established between 850 and 700 BC. The hilly location of a ford on the Tiber River made building a fortified city logical. And anyone who controlled such a city would be guaranteed to grow and be powerful.

The Kingdom of Rome had (surprise, surprise) a king. It wasn't a hereditary title, but rather elected for life. But this king did have a lot of power. There was also a chief priest, a chief judge, and a chief legislator. The kingdom also had a senate, but don't go thinking that automatically means "democracy." The senate had little power, and was comprised of noblemen appointed by the king. So much for transparency or checks and balances. There were six kings (not counting Romulus, who may or may not have been real) before the kingdom ended. The story (how much is history and what is legend I'm not sure right now, I'll have to dig more) is that the son of the last king (Lucius Tarquinius Superbus) raped a noblewoman, who then begged her father and other noblemen of Rome to seek vengeance (then committed suicide, so as to give Shakespeare something to work with). The senate then voted to abolish the monarchy and exile the king and his family. In its place a republic was founded.

While the deposed king attempted a number of times to overthrow the new government, the Roman Republic would last nearly 500 years. Instead of a king, elected for life, the citizens would elect two counsels each year. In a way it was a form of proto-presidency. The very same powers the king had, the counsels now had. The senate was still a non-elected and weak body, but later they would gain in influence.

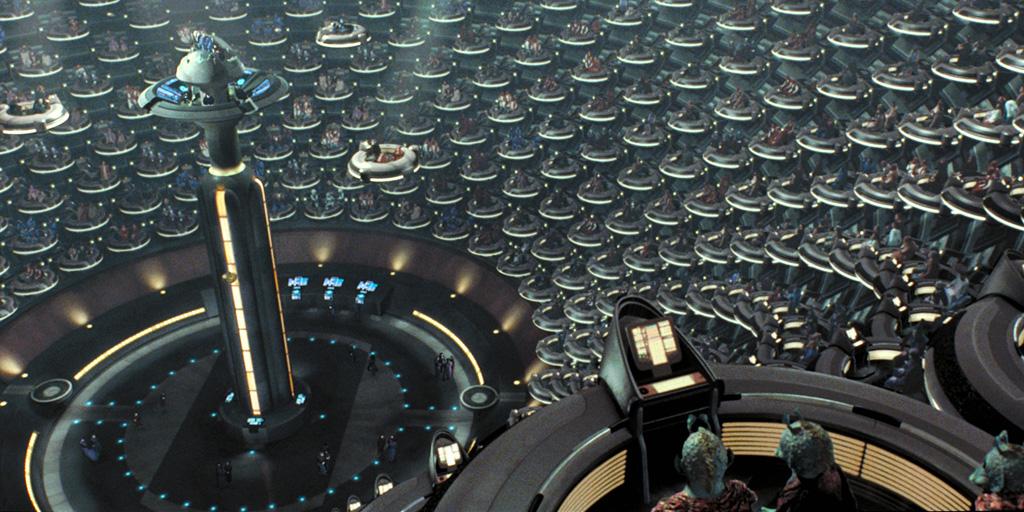

(The senate, in all its glorious chaos.)

The very chaotic nature of Republic politics led to a few prominent men to form an alliance to try to gain control. (Hmm, sounds a bit familiar... to all of government history.) The first triumvirate consisted of Pompey the Great, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Julius Caesar. The goal was simple: support each other to gain power and influence. With Crassus's death in 53 BC, the triumvirate ended. Pompey and Caesar started becoming more of rivals than partners. With Caesar gaining popularity in the military, the senate picked Pompey to stand against him. In 49 BC, Caesar crossed the "line in the sand" on his way to besiege and capture Rome.

(Hey, Julius! I dare you to cross this Rubicon.)

Julius Caesar became a dictator, restoring order to the government. In 44 BC, on the Ides of March, Julius was assassinated by a group of senators who feared (among other things) he'd reestablish a monarchy and take power away from land owners. Their plan failed, since Julius's great-nephew Octavian teamed up with Marcus Antonius and Marcus Lepidus to take control of the government. The senate remained basically powerless. Lepidus wasn't as big a player in this trio. Mark and Gus (Antonius and Octavian) would go on to fight for control. If you want to know how that all went down, I know there's a documentary written by some Englishman named Willy. Its supposed to be pretty good (even if the lead love interest wasn't that pretty).

(After Octavian took over, the streets were crawling with legions of soldiers.)

Octavian took the name Augustus, and the cognomen Caesar became a title synonymous with "emperor." In fact, the title emperor in a number of languages, including German and Russian, is the name caesar (kaiser and tsar, respectively). And from 27 BC until the fall of Rome to the Goths in 476 AD, the empire reigned supreme.

(An archive image of the caesar declaring the formation of the empire.)

Because of how especially long and complex the history of the Empire is (especially if we include the division set up by Constantine), I'm gonna take the lazy way out and skip it... for now. I may deal with it later, especially if I want to talk about the Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Empire, and so forth. Our goal here is the metaphor: the Roman soldier.

(Venimus. Videmus. Vincimus.)

I wish I could say that just looking at the Roman legions and their history simplifies things, but it doesn't. The campaigns, techniques, and reforms are just as complicated as the rest of this train-wreck. On the surface there seems to be no way to simplify this topic without leaving something important out. But if I don't want to write a thousand page doorstopper on this, I'll have to find a way.

(Is it terrible that I want to write way too much on this since the history helps formation of fictional stories? Is it terrible I don't care?)

For the sake of simplicity (in a way) and reducing the potential "tl;dr" commenting, I'll just stick to the army of the Roman Empire proper (27 BC - 400-ish AD).

The army was centered around the legion. Similar to divisions or regiments in modern armies, the legion had between 3000 and 5500 men (give or take, depending on era). Early on the legions were divided into centuria, each with 100 men and soldiers, and commanded by a centurion. The legions were the elite heavy infantry soldiers, while the remainder of the army was made up of auxiliaries. The auxiliaries were made up of non-citizens (unlike the legions) and provided a large portion of infantry and much of the cavalry force in Rome. Other units existed throughout the history of Rome, performing different tasks and missions.

A decent comparison between the two is the US Army vs. the US Marines; how they fight, deploy, organize, and even train are different. One is designed for hard-hitting, shock-and-awe expeditionary work, while the other is optimized for endurance fights, sieges, occupations and invasions using large stockpiles and resources. Maybe a better parallel would be from Star Wars. The Empire had the Army and the Stormtrooper Corps. The stormtroopers were elite, loyal only to the emperor, and the most visible representation of the Empire's might. The Army vastly outnumbered them, and had the resources (like AT-AT walkers) to back up that size. The "bucket-heads" even were divided into legions, such as the 501st.

(Members of the legion escorting emperor Lucas.)

(Incidentally, the 501st has a pretty cool story, both the in-universe version and the real one. That one from that galaxy far, far away is known for being Vader's personal legion, while the real one is even cooler thanks to being the inspiration for the fictional one, all while being a charitable organization. And make movie-worth costumes. Check them out here.)

(And, yes, I realize that this post is oddly Star Wars heavy despite not being about Star Wars. Blame Mr. Lucas for that, since the history of Rome influenced his story. I'll use more Star Wars metaphor in later posts on this subject anyway, since its such an easy visual to swipe.)

But we're here to focus on the "armor of God" metaphor, so we need to focus in on the kit of the average soldier. Yes, yes, I've done a little of this already, but one of the winning teaching methods is repetition.

Soldiers that were equipped with armor wore lorica hamata (mail), lorica segmantata (the stereotypical armor that looks like a lobster), or lorica squamata (scale armor). Officers often wore cuirass, the classic "muscled" breastplate, which was more costly than the other options and had less mobility to more protection.

The galea helmet was pretty well standard, with detail variations based on rank. Other helmet were worn, too, but the classic helm is the one we think of, horsehair crest and all.

Arm and leg armor would be worn too. The legs were protected by greaves, much like shin guards from football (better known as soccer in the States). A variety of arm armor was available, from full metal sleeves to forearm guards and gauntlets. Around the waist of the Roman soldier was the pteruges: a "skirt" of leather straps, which protected their upper legs and other sensitive bits.

The soldiers carried a sarcina, a rucksack, much like the MOLLE packs modern troops use to carry all their equipment.

A couple types of shields were common: the scutum and the parma. The parma was a three-foot wide circular shield, built on an iron frame of wood construction with metal reinforcements. They were replaced by the scutum, the classic shield we think of when we think of Rome. They were three and a half foot by a foot and a half (on average) and curved slightly. Lighter than the aspis, and providing larger protection, at the cost of strength, the scutum made the phalanx formation nigh unbeatable. If you've seen a modern riot shield, you've seen a scutum, basically.

At this point the guys in the audience are probably shouting "just get to the fun stuff already!" Obviously an army without weapons is just a group of men all dressed the same.

Spears were the main weapon (as you should see by now is the norm), and there were a few versions throughout history. The hasta was basically Rome's version of the Greek doru. There were javelins, which were the intended throwing spear. But the stereotypical spear was the pilum, with its extended iron shaft making it so that once it was thrown, it could not be recycled by an enemy soldier (due to the shaft bending once it hit something, like a shield or a Celt).

Bows, crossbows, darts, and slings were used as well. Often, as seen in other armies both before and after, these were used by "specialized" troops, though the sling was carried as a back-up weapon by all soldiers. The ammo was made of lead, and often stamped with slogans, much like how pilots in WW2 would "personalize" bombs.

(Because "take that" is always in style.)

But what about the stuff that goes "stabbity stab stab?" Well, obviously the spear should probably be here, since they stab, but I mean the close-in stuff. Swords. Rome had three kinds; well, technically two types of swords and a dagger. Though if you're a hobbit, the pugio dagger would make a fine short broadsword. The pugio was the dagger used by the conspirators who killed Julius Caesar. I'll admit, I think it looks like a trowel. Most of us have never heard of it, but we've probably heard of the gladius and the spatha.

The gladius is the traditional two edged short sword of the Roman Empire. About 24 to 30 inches long, it looks very similar to Bilbo Baggins's sword Sting. And, yes, Tolkien fans, I know that Sting is actually a dagger used as a sword. Notice what I said earlier about the pugio. But my comparison to Sting is mostly appearance.

The spatha, which seems to also be the generic term for "sword," describes a longer sword, about 30 to 40 inches. The design of the spatha led directly to the Migration Period swords (think what LOTR's Rohan carried) and the classic swords of knights and crusaders. I will go into detail later on those.

At the end of the day, the sword in the Roman army was for short range work. It was for times the fighting was so close you could smell your opponent's breath.

(General Pompous Maximus preferred a more "personal touch" to subjugating barbarian tribes.)

There is one last piece of kit to mention. And not because there aren't more items the average Roman soldier would carry, or because there aren't more weapons. The last, and arguably most important, piece of Roman military technology was the caliga: boots.

Healthy feet are extremely important in the army, especially the infantry. These things were pretty sophisticated. Designed to reduce blisters while on march, the thicker sole had hobnails to act as cleats, and the open design kept the soldier from getting trench foot. In fact, the patter the hobnails were placed in is almost exactly the same as the cleat pattern on cross country running shoes.

As a side note, Roman emperor Gaius Caesar, who reigned from 37 to 41 AD, is better known as "Caligula." He gained this nickname when he was two or three while spending time with his father, a general, and the soldiers made him small boots. He didn't like the name.

We'll look at Rome again once we dig back into the metaphor itself and try to discern why (or at least why I think) Paul used the details he did. And, yes, I think each was intentional.

And there you have it. Next up: the era of classic knights.

No comments:

Post a Comment