But before I get into that, let's review the text first:

Finally, be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his might. Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil. For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. Therefore take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm. Stand therefore, having fastened on the belt of truth, and having put on the breastplate of righteousness, and, as shoes for your feet, having put on the readiness given by the gospel of peace. In all circumstances take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming darts of the evil one; and take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, praying at all times in the Spirit, with all prayer and supplication. To that end keep alert with all perseverance, making supplication for all the saints, and also for me, that words may be given to me in opening my mouth boldly to proclaim the mystery of the gospel, for which I am an ambassador in chains, that I may declare it boldly, as I ought to speak. Eph 6:10-20 (ESV)Now, on to the historic reality.

Granted, I am skipping some historic examples, such as the heritage of Japan, and the Renaissance-era. That's in part for simplicity and in part because I'm sticking to the iconic and stereotypical image for later use. And even then, I'm aiming for a narrow portion of the Middle Ages, since this is a thousand years (give or take) of dynamic history and if I don't I'll end up writing a doorstopper. (Not that I'm opposed to that, but I've got other stuff to tackle too, and no one wants a "tl;dr" situation.)

Then again, I could just toss you over to the work of Mike Loades (among others) who researches this era almost exclusively. (Link to his special, Going Medieval, is here.) His series on weapons will be used as resource later on as we dissect the image. But enough of that, let's do this.

The Medieval period. The Middle Ages. The Dark Ages. Whatever you call it, it was anything but boring. This era saw:

- the chaos of the fallen Roman Empire in the west,

- the legends of the King of the Britons: Arthur,

- the histories (both real and mythical) of Charlemagne,

- the schism of the Eastern and Western church,

- the "game of thrones" as the Holy Roman Empire coalesced in Germany,

- the campaigns to conquer and reconquer the Holy Lands,

- the attacks of the "northmen:" the Vikings,

- the threat of the Mongols to the far east,

- the incursion of the caliphate in Spain, Italy, and the Near East,

- the War of the Roses,

- the "duel of fates" that the English and French were locked in for centuries,

- the joust,

- the might of the castle,

- the beauty of the cathedral,

- the feudal system of government and agriculture,

- the rise of Shakespeare,

- the dark legacy of tyrants like Vlad III: the "Impaler,"

- the voyages of Marco Polo,

- the legacy and riches of the Silk Road,

- the power and prestige of the Church,

- and most ominous of all, the Black Death.

(The cheeky grin may not be historically accurate, but "A Knight's Tale" is still a good movie.)

In spite of being relegated (unfairly) to the trash bin of history as a backward and unintelligent age, the Medieval period still conjures up images of chivalric heroes fighting insurmountable odds to save the honor of a young maiden. Our sense of honor, romance, and adventure lead us back to this time, at least in fiction. Guided by giants like Tolkien, we see the lone knight on horseback as the apex of what a hero is. And it is for this reason that I'm using it as a metaphor overall. (If Fisk can have ninjas, and Rosebrough can have pirate, I can have knights.)

But before I dive into that, lets see if I can give y'all an explanation of 500-800 years of history.

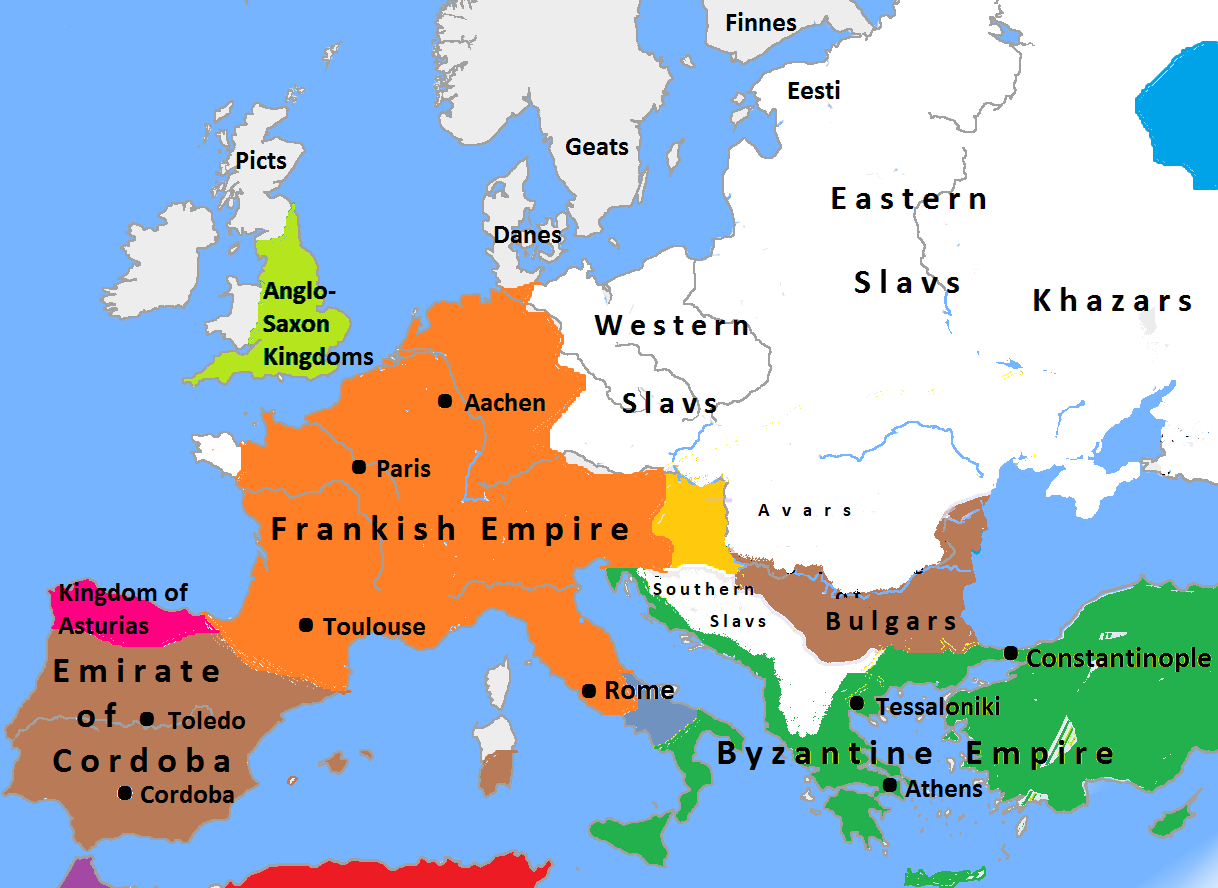

Conventionally and classically speaking, the Middle Ages focuses on the so called "western world." This means all the stuff from the border of the old Soviet Union to Spain, Sicily up to Sweden. It it was once owned by France, Spain, Britain, Germany, Denmark, or Italy it is part of the "western world."

(Now that's not to say the "western world" doesn't encompass more area. Poland, Ukraine, Greece, even Russia are the "western world," as opposed to the Middle East, the New World, Africa, or the Orient. However, since the classic knight didn't live in these areas, we'll ignore them for today.)

With the fall of Rome in 476 to the Ostrogoths, everything east of the Oder river fell into tribal warfare and chaos. The only unifying feature at that time, and the only authority that most were willing to follow was the Church. The Christian world was divided into bishoprics, much like the Roman Catholic church today has diocese. Above all the bishops (around 350 in the 4th century) were five archbishops in the five largest cities: Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, Jerusalem, and Rome. Four of these were in the "Eastern Roman Empire" (caused by Constantine's administrative decision to divide the empire). The bishop in Rome was in charge of the churches in Italy, Germany, Gaul (France), Iberia (Spain), and some of North Africa. With this much power (for good or ill), it was clear that whoever wanted to control the western Roman world would need the bishop of Rome to be supportive.

The man who ultimately found that support was Charles the Great - Charlemagne.

(Yes, he's on your playing cards. That's how influential he was.)

Now, before I get to Chuck, who gets his start in the 800s (ish), let me briefly set up a pair of substantial influences of the era: Islam and monasticism.

Islam was founded in the 600s by a failed and illiterate merchant in present day Saudi Arabia. By the 800s the Umayyad caliphate controlled everything from Morocco to Pakistan. All of North Africa and the whole Middle East except for Turkey. This would put pressure on the Christian world in places like Spain, Sicily, and the Empire Formerly Known As The Eastern Roman Empire (the Byzantines, in Greece). This international threat would culminate in the Crusades. But that mess is after Charlemagne, so be patient.

Monasticism should be a little familiar: monks living in austere conditions teaching secret and mystical things.

(I'm not sure if you are serious... or if you are trolling me.)

Okay, so what I described was a more "eastern" style of monasticism (which did influence the Star Wars universe). In Christendom the idea of monasticism was fairly early, with Anthony being the "founder." Certain people saw fit to remove themselves from society to spend time studying, praying, and providing works of service. Quickly, though, this became a form of works-righteousness. People began seeing monks (and nuns) as holier than thou, because they spent their whole lives praying and fasting. A number of orders would be founded: Augustinians, Benedictines, Cistercians, Dominicans, Franciscans, Hospitallers, Jesuits, Templars. Some set up schools, while others worked hospitals. Some would preach on street corners, while a few would fight pagans. People would even "donate" children to the monastery. The church became an industry and a world power thought this build-up.

This is the world of Charlemagne.

Gaul had been divided into three kingdoms, with plenty of in-fighting, back-stabbing, and horse-trading/stealing. Princes, dukes, earls, counts, and other petty nobility ruled territories within. The world was divided into manors, and each little town, territory, and county was as if its own small nation-state. This is a very complex game of thrones that ends on Christmas Day, 800 AD, with the coronation of Charles the Great as the first Holy Roman Emperor. He is seen as the father of Europe, and this is the turning point of the Medieval era. Europe was united (mostly) and a renaissance of art and learning occurred.

(Charlemagne owned the orange stuff.)

The Carolingian empire would last until 888, when Europe was divided again, essentially into France and Germany.

In the British isles the Angles and the Saxons fought with the Picts and Celts, only to be fought off by the Norse, and later the Normans. A lot of what is thought of as "knight classic" in England and America comes from the histories of the British isles (coconuts not included).

The Norse (better known by us as Vikings) played quite a role, and were very influential on history. I'll probably do just a history post on them, since it is very interesting, and much less barbaric than we've been led to believe. (They were still very barbaric, though, but they did have a reasonably sophisticated society.)

Things get complicated between 900 and 1100. The number of kingdoms is greater, the Muslims (sometimes called Saracens or Mohammedans in older resources) had taken control of Spain and Sicily, the Viking threat was diminished but had damaged northern Europe (not to mention they'd explored all the way to Vinland). The Byzantine empire was in dire straights, and sought help, even though the Great Schism had occurred in 1054 (which I alluded to earlier). To aid fellow Christians, and defend the holy city of Jerusalem, not to mention get those knights doing something useful instead of pillaging like a bunch of gang members in a low-riding Cadillac, the papacy supported and even sanctioned crusades.

(He belongs in a museum.)

Now, I'm gonna take the lazy way out regarding the Crusades. Not because it isn't an interesting and important topic, but because if I don't we'll never get to the kit of the classic knight. So I'll defer to one of my old professors, Dr. Matthew Phillips, one of the history professors at Concordia University in Seward, NE (my school). He was on Issues ETC discussing the Crusades and gave a very good primer covering them. (It should be good, he teaches an entire course on the topic.) So, if you've got the time or desire, give them a listen. The Crusades (five parts)

The Middle Ages after the Crusades was dominated by the French, the British, and the Holy Roman Empire. The French and British spent a lot of time fighting over what is now west France, which is why you see a bunch of Brits wandering around France in "A Knight's Tale." This is the Hundred Years War. It is this era, and the dynamic and rapid changes in technology, society, and even language, that brought about the Renaissance and Reformation. If you've seen a Renaissance fair, or watched any of Mike Loades work, then you've at least a decent visual of what the era looked like. Things like "The Tournament."

The Black Death was probably the "last straw" in the transition from the Middle Ages to the "modern era." At that point things weren't going back. The plague was brought into Europe due to the influx of trade, which had become the next "big thing." Marco Polo is the most commonly seen instigator of the Age of Discovery, which ended up with a lost Italian in the Caribbean starting the Spanish conquest of the New World.

And in the midsts of all this was war.

Castles, archers, sieges, trebuchets ("which can launch 90kg projectiles over 300m"), jousts, and, most of all, knights.

So, I'm just gonna get right to it and skip all the other fun stuff. (Don't worry, I'll probably revisit it later. Or you can just do some digging yourself.)

(An example of a knight hospitaller from the Crusades.)

Where to start? Weapons or armor? Weapons or armor? Well, being germanic of heritage, I'm nothing if not consistent. So I'll let my compulsive Italian side lead the way. Weapons it is.

The sword.

Oh, you wanted more? Okay, then.

There are swords and knives (like the seax, dirk, dagger, longsword, short sword, claymore, arming sword, bastard sword, saber, falchion, and viking sword), pole arms (like the spear, halberd, pike, lance, glaive, and scythe), melee weapons (mace, morning star, flail, battle axe, quarter staff, maul, and war hammer), and ranged weapons (like the longbow, recurve bow, Mongol bow, crossbow, sling, francisca, javelin, and musket). This doesn't include siege weapons (like trebuchets), warships (like carracks), and fortifications (like castles). And that's just from Europe. There's still all sorts of unique and interesting arms from every other continent (things like the katana, the atlatl, and the leiomano).

Since swords are the iconic weapon of a knight, I could (and probably should) go into great detail about them now, but I'll save that for later. Same with shields, even though they took on a variety of roles in this era (heraldry, anyone?).

But the armor is where its at. I will be going into greater detail as I dissect the metaphor (and take my own spin on it), but how about some "bird's eye view" history? Ya know, since suits of armor haven't been in style since the 17th century. (Unless you're a frequenter of Renaissance fairs.)

(The basic components of a classic suit of armor.)

Plate armor, specifically steel plate, wasn't easy to build early on. Mail (worn over a gambeson or aketon) and scale armor shirts (called a brigandine or jack of plates) were the "cheap" version. Padded shirts, like aketons, would be worn under later plate armor as well. If you've watched "The Two Towers," specifically when Aragorn is getting ready for the battle, the way he dresses and the armor he wears is actually petty accurate, especially for the 10th-11th centuries.

Mail and scale were not defense against pierces, but blunt force and shrapnel. Plate armor was developed to halt arrows, spears, and swords. Late versions were designed to halt bullets as well. In fact armorers would take practice shots against armor, then mark where the armor was proof against bullets. (Bulletproof... get it?)

Not all plate armor was the same. The armor on the chest and head was stouter than on the arms and lower legs. The shoulders, elbows, and hands had multiple joints and bends to allow for movement, but these were also weak points. And armor was heavy, but not so heavy as to make the knight immobile if knocked down. Not more than the average total carried by the average American soldier (about 75 lb), though the weight was better distributed, instead of being primarily in a rucksack.

But, like past armors, this stuff was costly. In the high Middle Ages (late 1200s until 1600s-ish) there were two types: Gothic and Italian. The Gothic style was much more detailed, with Maximilian style being the most intricate and artistic. Italian was simpler, thus a little less expensive. Despite this, and the advancements made in metallurgy, the only people who could afford such military kit were the nobility. Most soldiers would be lucky to have mail. Few would have had swords, at least if the were peasants. That's not to say all knights were of great wealth. Many were what we would today call "upper middle class." They can afford the new iPhone and a mortgage and go out of a fancy restaurant a couple times a month, but they don't drive Aston Martins to their third home in Beverly Hills. Some knights would go on to become the nouveau riche who would provide substantial influence in the Age of Discovery, the Age of Enlightenment, and the Victorian Era.

I could go on, but then I'd just repeat myself when I over-analyze this stuff later. And I will, since I'm taking the metaphor of "the Armor of God" and running with it. So explaining the various parts of the kit, in detail, will be in the future. Near future? Maybe.

No comments:

Post a Comment